The Thaddeus Stevens & Lydia Hamilton Smith Center for History and Democracy

By Mary Hendriksen

December 12th, 2024

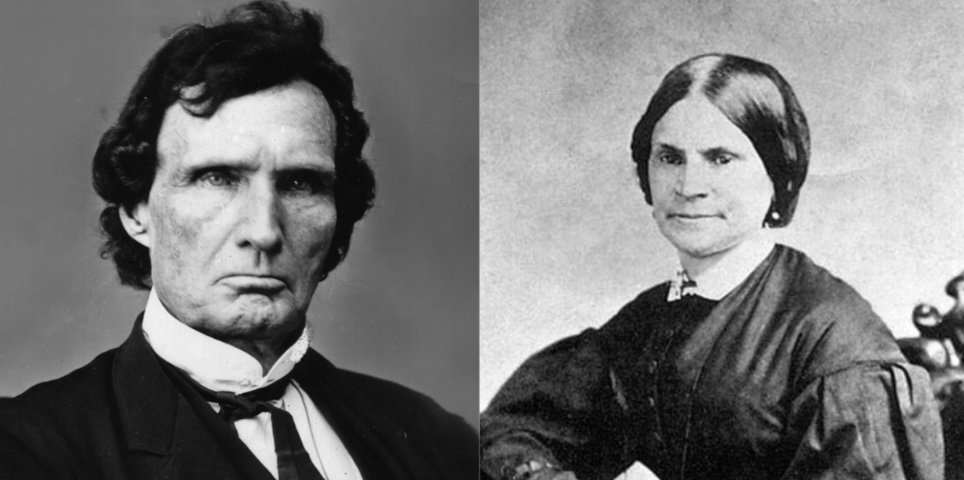

At a time in our nation’s history when democracy is in peril, as well as a time when issues of racial and ethnic identity seem ever more complicated and contentious, a group of historians, scholars, humanists and activists in Lancaster, Pennsylvania are working to focus attention on how the entwined efforts of two people—Thaddeus Stevens and Lydia Hamilton Smith—advanced the long, arduous struggle for freedom and equality in America.

Their endeavor: The Thaddeus Stevens & Lydia Hamilton Smith Center for History and Democracy, an interpretive museum and education center that is scheduled to open in 2025.

While the name of Pennsylvania congressman Thaddeus Stevens, a fervent abolitionist and the architect of the 13th, 14th , and 15th amendments, may be familiar to many Americans, the name Lydia Hamilton Smith is most certainly not. Museum organizers, one of whom is a founding board member of AAIDN, Lenwood Sloan, are working to change that.

How to describe Lydia Hamilton Smith?

“Certainly as an incredible Afro Gaelic woman who was a full partner with Stevens in the fight for equity, parity, and justice,” says Sloan.

The more schematic outline,” he continues, “is that Lydia Hamilton Smith was born in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania—right on the border of the free state of Pennsylvania and Maryland, where slavery was legal—in the year 1815. Her mother, Mrs. O’Neill, from Irish Town, was mixed-race and Catholic; her father, Enoch Hamilton, was Scotch-Irish and worked at Russell’s Tavern.”

This time before the Civil War was dangerous for free Blacks. Smith moved with her husband, Jacob Smith, from Gettysburg to Harrisburg, along with their two sons, William and Isaac, in 1840, when she was 25 years of age. That move was probably to escape kidnapping.

“There are endless documented cases of Black people being apprehended and then stolen away as they tried to enjoy the first fruits of freedom in Pennsylvania,” says the University of Maryland historian Richard Bell in an article in Smithsonian Magazine on Stevens, Smith, and the new center. “Not only did enslavers pursue fugitives, but there was also a reverse Underground Railroad, where predators kidnapped legally free Black people, often children, and sold them south into bondage.

Lenwood Sloan

At a time when women were not legally allowed to own property, Lydia Hamilton Smith owned property with her husband in Harrisburg and, some time after she separated from him, moved to Lancaster in 1844 to be the housekeeper for Stevens.

But the term “housekeeper” does not begin to describe her role in Stevens’ home or her achievements both with him and on her own, Sloan emphasizes.

“She was the confidante and quartermaster for Thaddeus Stevens while he crafted and advocated for the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments. Not insignificantly, she was his caregiver as well. She navigated the world for Stevens as his mobility worsened in the last years of his life, when the work to ratify the amendments was most critical. For example, she hired a coach service to transport him to Congress from Lancaster, and then hired men to physically carry him into House chambers when he could not walk. She bought and ran a boarding house across from the Willard Hotel in Washington, as well as a second home, where Stevens lived when Congress was in session.”

Given this multiplicity of roles, “companion” is the word Sloan believes best describes Smith.

“The Latin root of ‘companion’ is “companio,” he explains, “to break bread [‘pa nis’] together.”

During her years as Stevens’ companion, Smith mingled with the nation’s most influential politicians and drew national attention.

After Stevens’ death in 1868, Smith continued to live in Lancaster. She broke social barriers to achieve remarkable influence and wealth.

A landlord and business owner in a challenging era for women, especially Black women, Smith owned several properties and filed lawsuits to defend herself and her property.

“She could have passed for white,” Sloan asserts, “but she did not. Smith always identified as a free woman of color. That is just one reason the story of her life is important to AAIDN, an organization that holds as its center the importance of claiming, and honoring, all of one’s identities.

“Equity, parity, justice,” Sloan says again. “Smith’s alliance with Stevens is built upon her demonstration of how the post-Civil War amendments can achieve each of these ideals. Of course, Smith did not live long enough to benefit from the 19th amendment, which gave women the right to vote.

“Up until now,” he continues, “history has measured Smith, when it actually does acknowledge her, as a ‘moon’ to Stevens between 1844 and 1868. In fact, she was the example and achievement of his life’s work. One goal of the new center is to demonstrate how many lives she touched and causes she supported.”

More broadly, with the work of achieving equity, parity, and justice for all Americans far from over, the Thaddeus Stevens & Lydia Hamilton Smith Center for History and Democracy will combine historic buildings (Stevens’ law office and the Stevens/Smith home) with a state-of-the-art museum to examine the lives and legacies of Stevens and Smith, and their social networks of abolitionists. In interrogating and honoring a rare working relationship of close respect across color and gender lines, the Center’s multi-faceted exhibits—developed in partnership with world-renowned museum designers and noted historians—will address issues of slavery, freedom, and the continuing fight for equality in the United States. It will seek to promote democracy in action by connecting freedom struggles of the past and present, all with the goal of emboldening visitors to make positive change in their communities.

READ MORE: https://stevensandsmithcenter.org/lydia-hamilton-smith/

Donate to the organization Lancaster History to support a statue of Lydia Hamilton Smith.