Marcus Garvey: His legacy, and his connection with Ireland and Irish America

By Mary Hendriksen

February 10th, 2025

Portrait of civil rights leader Marcus Garvey

Overview of the Life and Contributions of Marcus Garvey

One of the most influential leaders of the 20th century’s civil rights movement was Marcus Garvey, born in colonial St. Ann’s, Jamaica in 1887—a time at which empires, including the British Empire, were crumbling.

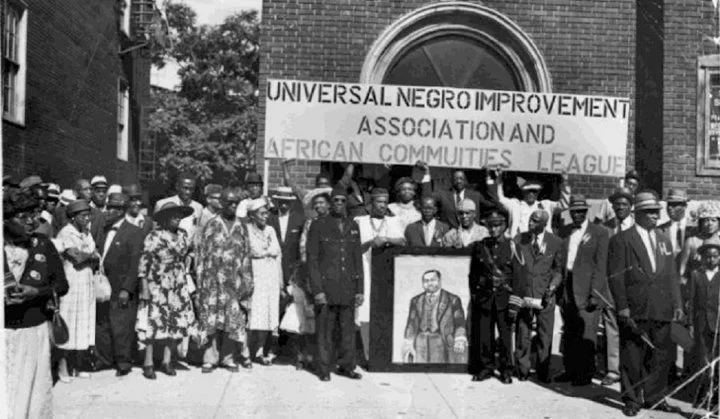

After spending some time in London, Garvey came to the US in March 1916. In New York City’s Harlem, his fledgling United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) grew. Its aim was to unite Black people around the world. The UNIA’s motto was "One God! One Aim! One Destiny!" and its slogan was "Africa for the Africans, at home and abroad!"

The charismatic Garvey grew the UNIA to encompass millions of members in 40 countries, with Garvey being called “the Black Moses” by many. Later, Martin Luther King Jr. described Garvey as “the first man of color in the history of the United States to lead and develop a mass movement. He was the first man on a mass scale and level to make the Negro feel he was somebody.”

Garvey’s message of Black separatism and his goal to repatriate to Africa was controversial—including among some of his Black contemporaries.

His fame and activities brought him to the attention of J. Edgar Hoover, who set in motion a conviction of mail fraud in 1923 in connection with the finances of the UNIA’s Black Star Line. That prosecution has long been seen as corrupt and racially motivated. Garvey served two years in prison, with President Calvin Coolidge commuting his sentence in 1927. He was then deported, though he continued to work to advance the goals of the UNIA until his death in 1940.

Marcus Garvey and the United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA)

The day before he left office, on January 19, 2025, President Joe Biden issued a posthumous grant of clemency for Garvey. Garvey’s family and many in the civil rights community had advocated for this action for decades.

Marcus Garvey’s relationship to Ireland and to Irish America

Garvey had a deep and unique relationship to Ireland and to Irish America. Dr. Miriam Nyhan Grey has explored this topic in a chapter titled “Marcus Garvey’s Irish Influences” in The Irish Revolution: A Global History, Patrick Mannion and Fearghal McGarry, eds. (New York University Press, 1922).

Dr. Grey recounts Garvey’s time in England and how it influenced him—explaining that it was in this period that Garvey “had his first sustained encounters with the Irish question and anti-imperialism more broadly.” Yet, at that time, Garvey still considered himself very much a subject of the British Empire, even urging his countrymen to fight for England during the First World War.

As for his arrival in the US one month before the Easter Rising, Dr. Grey provides context by describing New York City as “a very Irish city,” with a well organized diasporic community. In contrast, she says, Garvey “witnessed segregation and discrimination that politicized him on the issue of civil rights for African Americans.”

She recounts Garvey’s change from someone who believed in empire to the leader of an African separatist movement.

In the period 1918–1920, Garvey’s thinking shifted from empire to the related theme of race. His goal, rhetorically, was the establishment of an alternative type of empire defined by the racial solidarity of Black-ness, and in that sense the first theme directly feeds into the second, which had lingered in the shadows during Garvey’s wartime strategy of Blacks being seen to be well-behaved colonials. In refining its message of African redemption, the UNIA was influenced by both the changing international scene and the postwar wave of violence against African Americans. Between the summer of 1918 and the 1920 convention, Garvey established his plan for establishing an African republic, and it was precisely in this period that references to Ireland increased in his rhetoric, as Ireland and the Irish diaspora emerged as a roadmap for Garveyism. (340)

By December 1918, Garvey proclaimed: “The Irish, the Jews, the East Indians and all other oppressed people . . . are getting together to demand from their oppressors Liberty, Justice and Equality. . . and we now call [u]pon the four hundred million Negros of the world to do likewise.”

Further, Dr. Grey says: “[E]ven as Garvey was emphasizing Black solidarity, the Irish became his model for how to challenge an existing empire from within and supplant its authority with another type of empire.”

Indeed, when Garvey launched the Black Star Line at Carnegie Hall in 1919, he proclaimed:

“The Irish have been fighting for over 700 years to free Ireland. From the time when Robert Emmet, when he lost his head, to the time of Roger Casement, Ireland has been fighting, agitating and offering up her sons as martyrs.” And just as Emmet “bled and died for Ireland, we who are leading the Universal Negro Improvement Association, are prepared at any time to free Africa and free the negroes of the world.”

Dr. Grey concludes her chapter with these words:

Garvey’s encounters and interest in Ireland were galvanized by the dual and interrelated reach of empire and diaspora. For Garvey, Ireland, Jamaica, and Africa were connected to one another as components of the British Empire and as exponents of a diaspora nationalism espoused most visibly in New York City. An appreciation of how Ireland influenced Garvey, whose rhetoric and activism made the example of Ireland resonate throughout the Caribbean, Black America, and Africa, enriches the global dimensions of Irish history, while an Irish reading of Garvey also complements recent scholarship that has sought to place the impact of Garveyism in a more global framework, thereby counterbalancing Garvey’s marginalization within American historiographical debates. (348-349).

In addition to Dr. Grey’s chapter, for a succinct overview of Marcus Garvey’s life, see:

“Howard University School of Law Professors and Students Secure Posthumous Pardon for Civil Rights Leader Marcus Garvey,” January 19, 2025

“Marcus Garvey: Leader of a Revolutionary Global Movement,” narrated by Professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr., within the award-winning series Black History in Two Minutes.]